Ground Uncontrolled: Disaster to the Power of Ten

Our existence is hazardous. Our co-habitation invites danger. As technology permeates our space, a provocative dance between risk and safety is performed. On September 25th, 1978, the North Park neighborhood of San Diego was subject to ground level disaster from a midair catastrophe. GROUND UNCONTROLLED: Disaster to the Power of Ten indulges a curiosity for disastrous events like that of PSA flight 182 which saw its 727 collide with the Cessna it dwarfed and disembody on the residential grid below.

Objects of nostalgia and vernacular pay tribute to era, location and context of the event, pulling in adjacent cultural happenings, personas, writings, ephemera while exploring consequential musings in the world of art and theory. Using the computer interface as the skeleton for a design system, the morphology of the book is specifically derived from the path that the plane took from its in-flight status 30,000 feet above ground to the autopsy of its debris at a microscopic level. The book's design structure parallels the contents’ reflection on the breakdown of systems, as it is illustrated that the visual development of the book relies on the stability of computer software to come into being. The more the book elaborates on the historical disaster and systems of fragility, the physical design of the book begins to glitch and ultimately crash. In the end, we're confronted with society's acute reliance on the success of systems, a chilling reality exposed only by the response it has when they have failed.

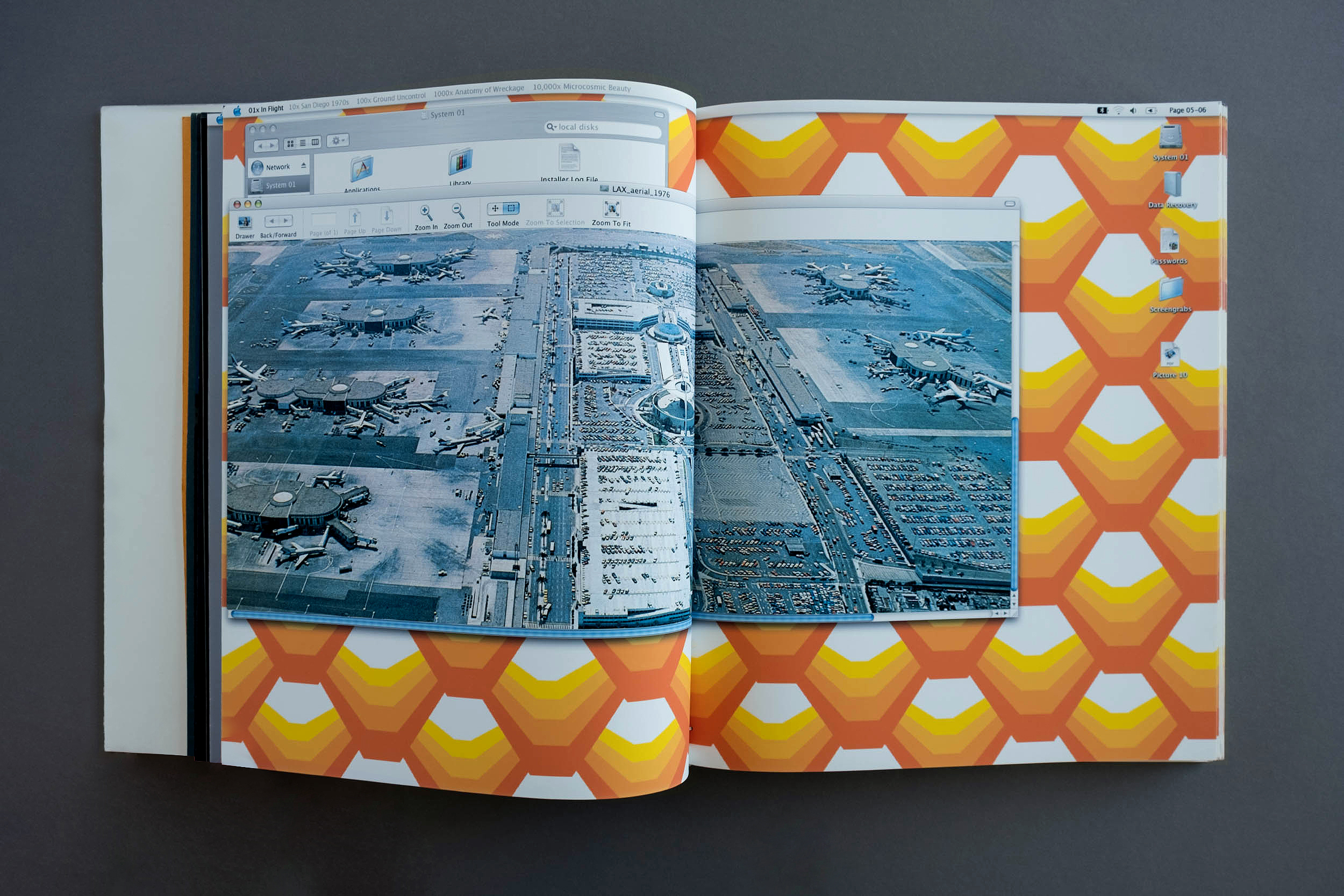

The design of the book begins with a magnification of 1x, and is titled In Flight.

The traditional way-finding systems of a book (page numbers, page titles, headers, etc.) are appropriated into the anatomy of a desktop interface.

The plane involved in the air crash was one inbound from Los Angeles International Airport headed for San Diego. The In Flight story begins with a historical photo essay of the two landmark airports in 1978.

The content of the book is an orchestration of personal and found artifacts, photographs and texts, stitched together through relevant texts from selected authors. Content that opens the book is compartmentalized with a strict rationalized organization. Each new piece of data introduced conforms to the display of the computer system.

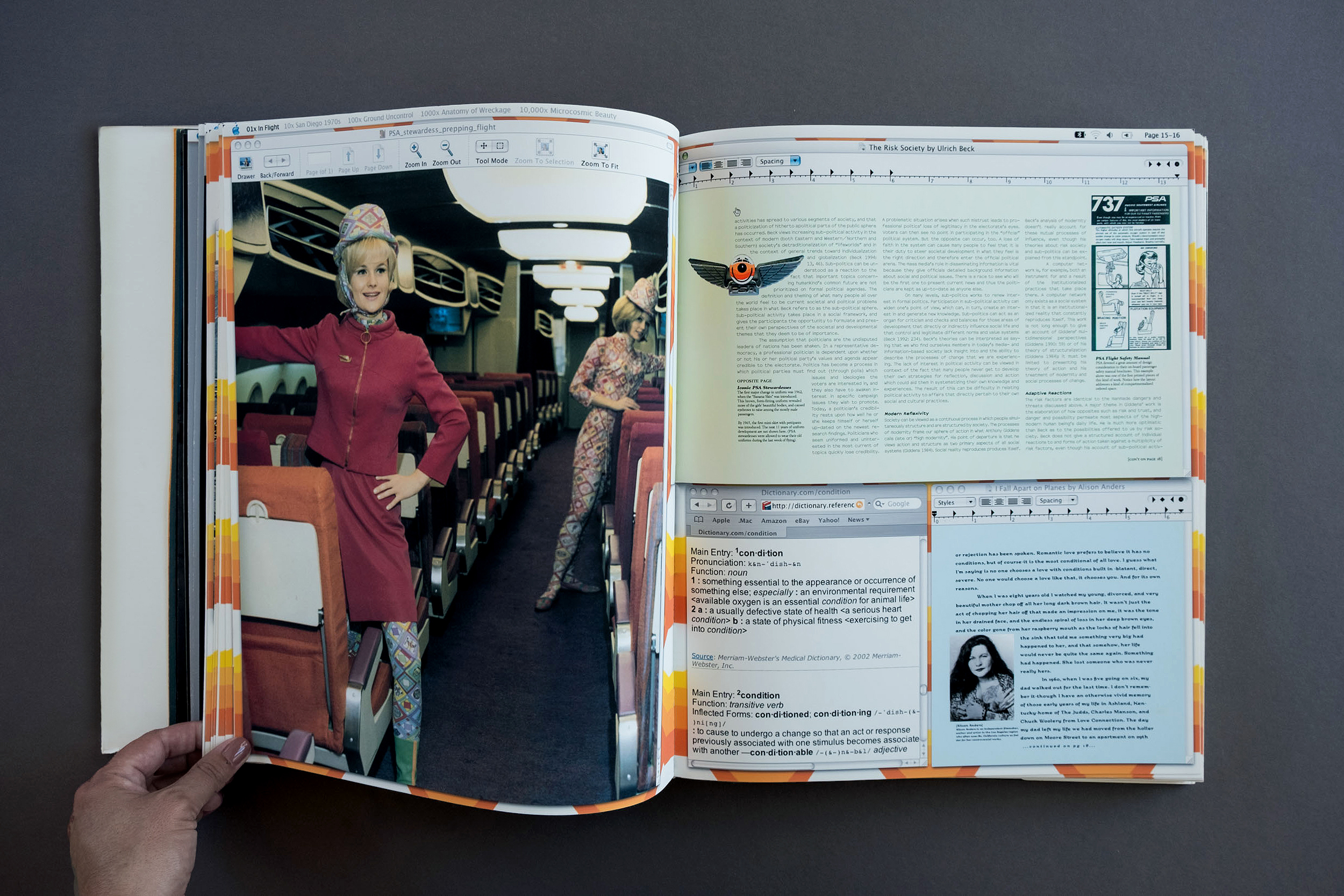

For example, quotes by particular authors are presented in the form of an instant messaging window, definitions of terms via an online dictionary and factoidal “STATS” presented as system notifications.

In Flight deconstructs airline culture, consumers' psychological relationship to air travel, and the industry’s influence on food, fashion, personal space and social hierarchy.

It describes airline culture as one of the great scripted spaces, where even the smallest surfaces have a codified language and an international identity.

Chapter two, 1970s San Diego, magnifies the event by 10x. Prior to crashing, the 727 was preparing to land at San Diego International Airport, circling over the near downtown neighborhood of North Park, where my family’s modest home was. This chapter was used as an opportunity to recapture the cultural climate of the southern California city in the wake of the 60s and 70s counter-cultural milieu.

The Boomtown Rats had a chart topping song titled, “I Don’t Like Mondays”, a lyrical account of Brenda Spencer, the infamous teenage school shooter who opened fire on a San Diego elementary school. While the incident inspired the popular new wave hit, the new social paranoia toward the school environment as a dangerous space has had greater permanence.

Woven texts in this section both romanticize and warn of Southern California as a threshold for disastrous events, both natural, psychological and technological. Mike Davis’ Our Secret Kansas is featured as a critique on social phobias and ecological hysterias, conditions he sites as indicative of Southern California’s relationship with, cultural, technological and ecological instability.

Pop-cultural hurricanes are adjacently highlighted, pointing out that the late controversial Lester Bangs was a native San Diegan who penned much of his toothy cynicism for the music industry from his hometown studio, also the original publishing location of his influential Creem Magazine.

1970s "muscle car" design solidified the automobile as a symbol of sexual power and aggression. Particular to this era, B-cinema cast the automobile as the perfect device for high-risk chases, the site of graphic teenage massacres, and the possessed machinery antagonist capable of supernatural powers as in Stephen King’s Christine.

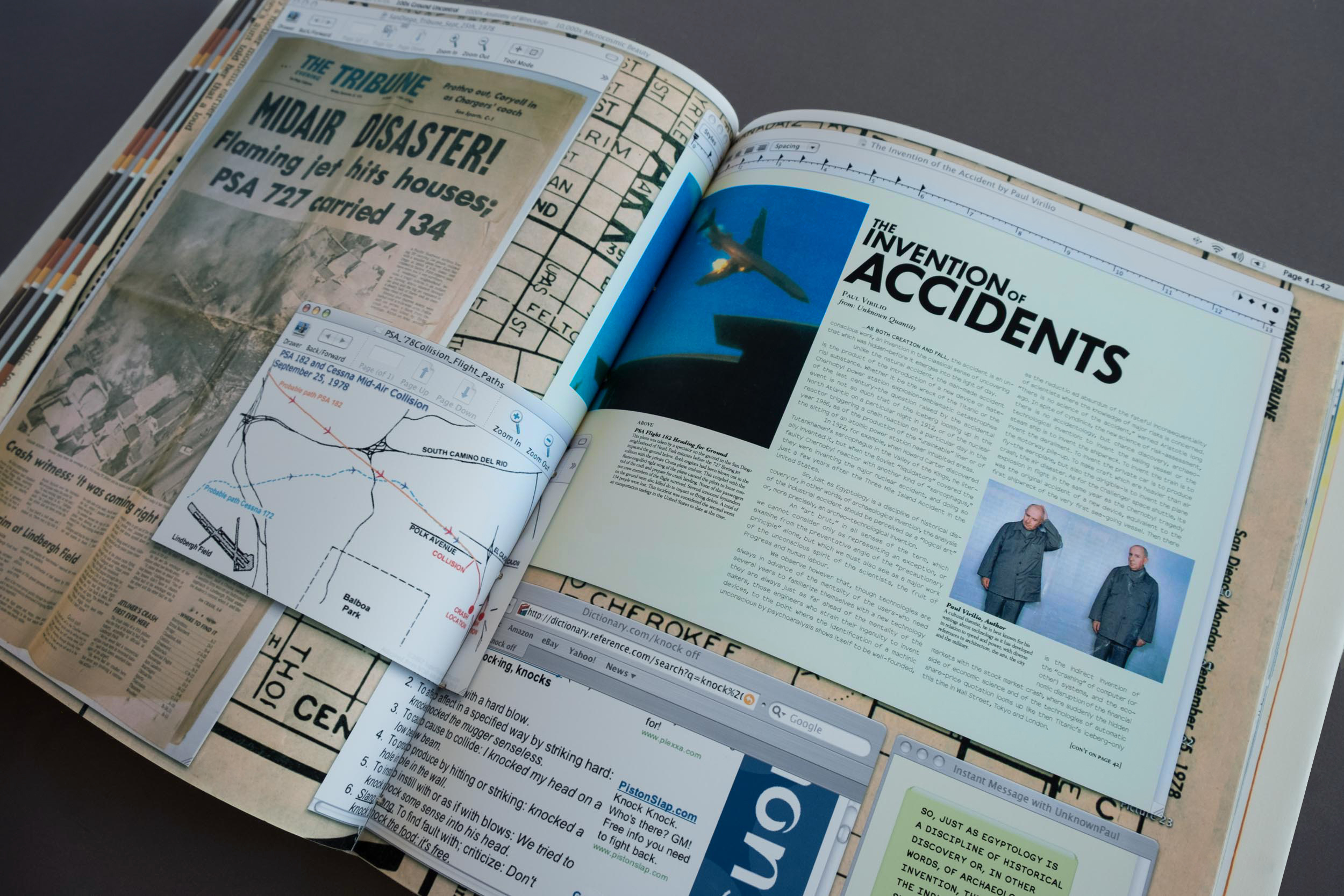

Magnification by 100x bears witness to the advent of the mid-air crash. Due to substandard sighting abilities, the 727 collided with a small 2-passenger Cesna prop plane it could not see. Both planes lost engine power and collided on the neighborhood below.

A shift occurs in the previously ordered design of the book. System windows are no longer compartmentalized, opening and collapsing to make way for new content. Instead, the grid begins to incrementally fall apart as content crowds the frame of the book with layered intensity.

In total, over 130 people died, there were no survivors. The ichat window to the left quotes Paul Virilio from his book Unknown Quantity,

“To invent the sailing vessel or the steam ship is to invent the shipwreck. To invent the train is to invent the derailment. To invent the private car is to produce the motorway pile-up, to make craft which are heavier than air fly-the aeroplane, but also the dirigible-is to invent the plane crash, the air disaster.”

At magnification 1000x, Anatomy of Wreckage draws parallels between the expiration of human experience and the finite lifespan of technology’s "biology."

An excerpt from the Donnie Darko film script is included to offer a metaphor for this paradigm, “The falling jet engine approaches the hexagonal plate of light which accelerates downwards...forming a tunnel with walls made of swirling liquid marble. The jet engine passes into the hexagonal plate. In a series of inter-velometer time-lapse shots...the entire suburban landscape retreats backward in a fury of speed.”

Comparison of two different autopsies — the left shows remaining fragments of a Pan Am Boeing 747, the victim of a terrorist bomb.

The right is a photo of Lisa McPhearson’s autopsy, "a member of the Church of Scientology who died of a pulmonary embolism while under the care of...a branch of the Church of Scientology. Following her death, the Church...was indicted on two felony charges, 'abuse and/or neglect of a disabled adult' and 'practicing medicine without a license'." -Wikipedia

The layering of system windows becomes more chaotic, maximizing the computer's available memory.

Another notable shift in the evolution of the book and presentation of content has occurred.

The foreground presents a set of compared images. The top row are black and white drawings hypothesizing the trajectory of a structural collapse from Lebbeus Woods’ installation, The Fall. The lower row are x-rays of a human body.

The sets eerily share similar form and composition, the human body’s structural DNA closely coded with that of a collapsing building.

While proposing compared fragilities, the computer has alerted the book that is has run out of memory and cannot continue to function properly. Data is lost in adjacent windows where previous texts displayed.

Finally, Microscopic Beauty magnifies the event by 10000x. The investigation leaves the visible surface going deep into the abstract microcosm of disaster and accident. In parallel, the computer system with which the design of the book is relying on is failing rapidly, and its interface begins to glitch, the system literally crashing, while program code (the microbes of the system) are exposed.

The content reaches a state of distorted abstraction as the texts have also become highly theoretical.

James Chiles’ essay, “That Human Touch” relates, “This kind of power, so easily taken for granted now, lets minor errors wreak major havoc in ways undreamed of during the horse and buggy days. Such errors can be the same kind you’ve made often: aiming for one button and hitting another, neglecting to do something you had meant to, taking an impromptu shortcut.”

Before the system completely shuts down and book language and content are eaten away by a forced curtain of stretched pixels, the last text submits with, “Ordinary language is loaded with redundant information not because we love to repeat ourselves but because speech is often misunderstood. Repetition pounds the information through the barriers of noise and distraction.”